For more information about medical misdiagnosis of the gifted, please visit the SENG Misdiagnosis Initiative page.

Many gifted and talented children (and adults) are being mis-diagnosed by psychologists, psychiatrists, pediatricians, and other health care professionals. The most common mis-diagnoses are: Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), Oppositional Defiant Disorder (OD), Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD), and Mood Disorders such as Cyclothymic Disorder, Dysthymic Disorder, Depression, and Bi-Polar Disorder. These common mis-diagnoses stem from an ignorance among professionals about specific social and emotional characteristics of gifted children which are then mistakenly assumed by these professionals to be signs of pathology.

In some situations where gifted children have received a correct diagnosis, giftedness is still a factor that must be considered in treatment, and should really generate a dual diagnosis. For example, existential depression or learning disability, when present in gifted children or adults, requires a different approach because new dimensions are added by the giftedness component. Yet the giftedness component typically is overlooked due to the lack of training and understanding by health care professionals.

Despite prevalent myths to the contrary, gifted children and adults are at particular psychological risk due to both internal characteristics and situational factors. These internal and situational factors can lead to interpersonal and psychological difficulties for gifted children, and subsequently to mis-diagnoses and inadequate treatment.

Internal Factors

First, let me mention the internal aspects. Historically, nearly all of the research on gifted individuals has focused on the intellectual aspects, particularly in an academic sense. Until recently, little attention has been given to personality factors which accompany high intellect and creativity. Even less attention has been given to the observation that these personality factors intensify and have greater life effects when intelligence level increases beyond IQ 130.

Perhaps the most universal, yet most often overlooked, characteristic of gifted children and adults is their intensity. One mother described it succinctly when she said, “My child’s life motto is that anything worth doing is worth doing to excess.” Gifted children — and gifted adults– often are extremely intense, whether in their emotional response, intellectual pursuits, sibling rivalry, or power struggles with an authority figure. Impatience is also frequently present, both with oneself and with others. The intensity also often manifests itself in heightened motor activity and physical restlessness.

Along with intensity, one typically finds in gifted individuals an extreme sensitivity—to emotions, sounds, touch, taste, etc. These children may burst into tears while watching a sad event on the evening news, keenly hear fluorescent lights, react strongly to smells, insist on having the tags removed from their shirts, must touch everything, or are overly reactive to touch in a tactile-defensive manner.

The gifted individual’s drive to understand, to question, and to search for consistency is likewise inherent and intense, as is the ability to see possibilities and alternatives. All of these characteristics together result in an intense idealism and concern with social and moral issues, which can create anxiety, depression, and a sharp challenging of others who do not share their concerns.

Situational Factors

Situational factors are highly relevant to the problem of mis-diagnosis. Intensity, sensitivity, idealism, impatience, questioning the status quo—none of these alone necessarily constitutes a problem. In fact, we generally value these characteristics and behaviors—unless they happen to occur in a tightly structured classroom, or in a highly organized business setting, or if they happen to challenge some cherished tradition, and gifted children are the very ones who challenge traditions or the status quo.

There is a substantial amount of research to indicate that gifted children spend at least one-fourth to one-half of the regular classroom time waiting for others to catch up. Boredom is rampant because of the age tracking in our public schools. Peer relations for gifted children are often difficult, all the more so because of the internal dyssynchrony (asynchronous development) shown by so many gifted children where their development is uneven across various academic, social, and developmental areas, and where their judgment often lags behind their intellect.

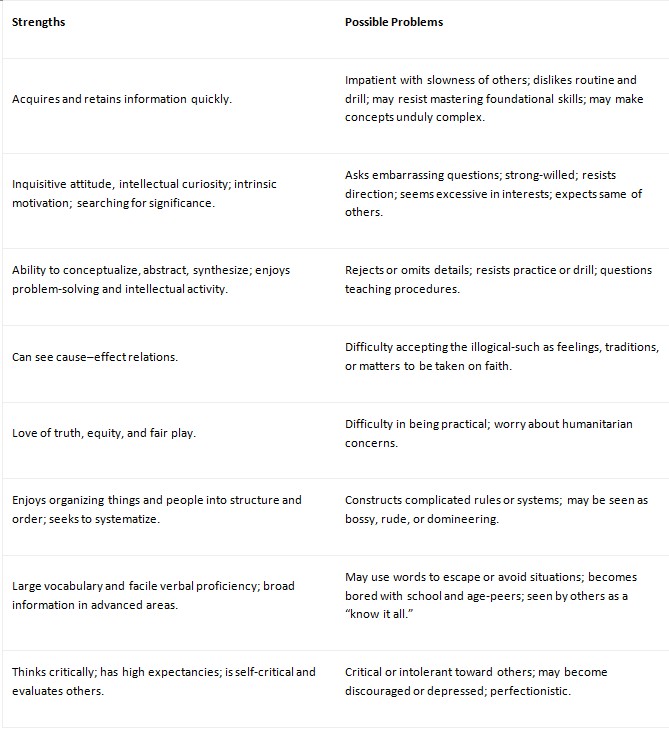

Clearly, there are possible (or even likely) problems that are associated with the characteristic strengths of gifted children.

Table 1: Possible Problems That May be Associated with Characteristic Strengths of Gifted Children (Continued)

Lack of understanding by parents, educators, and health professionals, combined with the problem situations (e.g., lack of appropriately differentiated education) leads to interpersonal problems which are then mis-labeled, and thus prompt the mis-diagnoses. The most common mis-diagnoses are as follows.

Common Mis-Diagnoses

ADHD and Gifted. Many gifted children are being mis-diagnosed as Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). The gifted child’s characteristics of intensity, sensitivity, impatience, and high motor activity can easily be mistaken for ADHD. Some gifted children surely do suffer from ADHD, and thus have a dual diagnosis of gifted and ADHD; but in my opinion, most are not. Few health care professionals give sufficient attention to the words about ADHD in DSM-IV that say “…inconsistent with developmental level….” The gifted child’s developmental level is different (asynchronous) when compared to other children, and health care professionals need to ask whether the child’s inattentiveness or impulsivity behaviors occur only in some situations but not in others. If the problem behaviors are situational only, the child is likely not suffering from ADHD.

To further complicate matters, clinical observation suggests that about three percent of highly gifted children suffer from a functional borderline hypoglycemic condition. Physical reactions in these conditions, when combined with the intensity and sensitivity, result in behaviors that can mimic ADHD. However, the ADHD-like symptoms in such cases will vary with the time of day, length of time since last meal, type of foods eaten, or exposure to other environmental agents.

Oppositional Defiant Disorder and Gifted. The intensity, sensitivity, and idealism of gifted children often lead others to view them as “strong-willed.” Power struggles with parents and teachers are common, particularly when these children receive criticism for some of the very characteristics that make them gifted.

Bi-Polar and other Mood Disorders and Gifted. Gifted children often go through periods of depression related to their disappointed idealism, and their feelings of aloneness and alienation can culminate in an existential depression. It is not always clear that such depression warrants a major diagnosis like Bi-Polar Disorder.

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder and Gifted. Even as preschoolers, gifted children love to organize people and things into complex frameworks, and get quite upset when others don’t follow their rules or don’t understand their schema. Their intellectualizing, sense of urgency, perfectionism, idealism, and intolerance for mistakes may be misunderstood to be signs of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder or Obsessive-Compulsive Personality Disorder.

Dual Diagnoses

Learning Disabilities and Giftedness. Giftedness is a coexisting factor in some diagnoses. One notable example is in diagnosis and treatment of learning disabilities. Inter-subscale scatter on intelligence tests increases as a child’s overall IQ exceeds 130. For highly gifted children, such discrepancy is far less likely to indicate pathological brain dysfunction, though it may suggest an unusual learning style and perhaps a relative learning disability.

Similarly, the difference between the highest and lowest scores on individual subscales within intelligence and achievement tests is often quite notable in gifted children. These score discrepancies are taken by most psychologists to indicate learning disabilities, and in a functional sense they do represent that. Gifted children may not “qualify” for a diagnosis of learning disability under some policies, yet they do show appreciable scatter of abilities.

Poor handwriting is often used as one indicator of learning disabilities. However, many gifted children show poor handwriting because their thoughts go much faster than their hands can move.

Psychologists must understand that, without intervention, self-esteem issues are almost a guarantee in gifted children with learning disabilities as well as those who simply have notable asynchronous development. Sharing formal ability and achievement test results with gifted children about their particular abilities, combined with reassurance, can often help them develop a more appropriate sense of self-evaluation.

Sleep Disorders and Giftedness. Nightmare Disorder, Sleep Terror Disorder, and Sleepwalking Disorder appear to be more prevalent among gifted children, particularly boys. Parents commonly report that their gifted children have dreams that are more vivid and intense, and that a substantial proportion of gifted boys are more prone to sleepwalking and bed wetting.

About twenty percent of gifted children seem to need significantly less sleep than other children, while another twenty percent appear to need significantly more. Some highly gifted adults report comfortably averaging two or three hours of sleep per night.

Multiple Personality Disorders and Giftedness. Though there is little formal study, anecdotal evidence suggests a relation between high intellectual abilities and the capacity to create and maintain elaborate separate personalities in MPD cases.

Relational Problems and Giftedness. Gifted children can be both exhilarating and exhausting. Because parents often lack information about gifted characteristics, relationships can suffer. Behaviors are sometimes seen as mischievous or strong-willed, prompting criticism or punishment for curiosity, intensity, or lag of judgment behind intellect.

“Impaired communication” and “inadequate discipline” are listed in DSM-IV as areas of concern in diagnoses of Parent-Child Relational Problems and Sibling Relational Problems. These are frequent concerns for parents of gifted children due to intensity, impatience, asynchronous development, and lag of judgment.

Health care professionals could benefit from increased knowledge concerning the effects of a gifted child’s behaviors within a family and thus avoid mistaken notions about causes of problems. The characteristics inherent within gifted children have implications for diagnosis and treatment which could include therapy for the whole family to develop coping mechanisms.

Conclusion

Many of our brightest and most creative minds are not only going unrecognized, but they also are often given diagnoses that indicate pathology. It is time that we trained health care professionals to give similar attention to our most gifted, talented, and creative children and adults so they do not conclude that certain inherent characteristics of giftedness represent pathology.

References

Clark, B. (1992). Growing up gifted: Developing the potential of children at home and at school. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, Fourth Edition. (1994). Jacobsen, M.E. (1999). Seagoe, M. (1974). Silverman, L. K. (1993). Webb, J. T., & Latimer, D. (1993). Webb, J. T. (1993). Webb, J. T. & Kleine, P. A. (1993). Webb, J. T., Meckstroth, E. A., & Tolan, S. S. (1982). Winner, E. (2000).